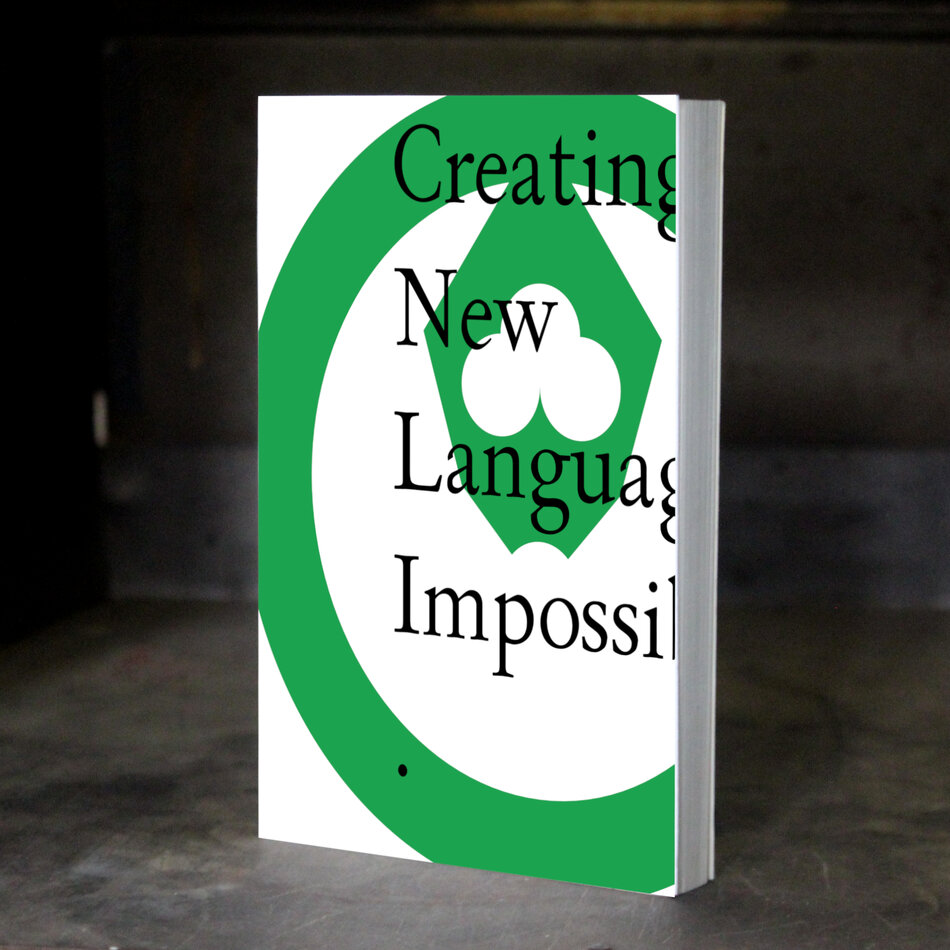

Creating a New Language: Impossible. (et vous êtes)

Portfolio Entry

One shared concept between western art and artificial intelligence is imitation.

Background

As an artist, I'm interested in technology from a critical point of view. I use technology as a theme and means to create new meanings about its impact on society. In this work, the creation of new meanings interacts with the sensemaking outcome of a storytelling process.

Artificial Intelligence technologies are considered part of the "most strategic technologies of the 21st century" [note 1]. Their role in social transformation appears similar to "the steam engine or electricity in the past" [note 2]. These technologies aim "to transform every sector of the economy and every aspect of our social lives" [note 3]. For those reasons, scholars stress the relevance of addressing the "potential economic, political and social costs" [note 4].

Imitating humans, not necessarily through mere duplication [note 5], appears to be one root behind Artificial Intelligence development [note 6]. Imitation is a long-standing topic in Western art [note 7]. One can think of imitation as a visual representation of reality (e.g. painting [note 8]). Likewise, one can think of imitation as a creation of human-like beings (e.g. sculptures able to move [note 9]).

One of the fields bridging narration of the creation of human-like beings and technologies is science fiction [note 10]. This kind of narration in science fiction often implies topics related to social themes such as labour (e.g. the idea of robots [note 11]).

I found these intersections intriguing and fruitful in developing artwork with elements of science fiction storytelling, yet distinct from a typical science fiction narration. Indeed, although the theme of my artwork revolves around "imitation and sympathy in art and artificial intelligence," the resulting outcome unexpectedly merges with the realm of science-fiction narration, revealing a captivating intersection that demands further exploration.

Clarifying Artistic Intent

Despite the outcome being a book with a science-fiction narration, the artistic process is not about the author's role in an artwork creation or social issues regarding the condition of cultural workers and the use of machines to produce narrative. Indeed, I aim not to create a narrative book written by an AI but an artwork that poses thought-provoking questions and explores new intersections with science-fiction narration and Artificial Intelligence technologies.

Unpacking the artwork

The artwork is within the frame of technologies and their potential social implications. The theme is at the intersection of imitation and sympathy. The subject is a new language, a science fiction storytelling and symbolic images created using an Artificial intelligence-powered computer program.

One needs information and instruction "arranged on the screen" [note 12] to use a computer program.»

The way used by this kind of computer program is an imitation of dialogue in human language via internet chat. It appears that the person who uses the computer program converses with the machine. This kind of imitation could drive sympathy toward the machine [note 13] and has societal implications [note 14].

What it looks like

The artwork looks like a printed book, downloadable file (171.0 kB) with the same content and a video.

The path I followed

Using Artificial Intelligence via dialogue in human language challenged me. I felt that imitation links to Western art tradition. Likewise, I knew that this idea made the machine fast and effective. Consequently, I put it in question but not entirely: I preserved the dialogue format.

Then, I tried to overcome human language imitation.

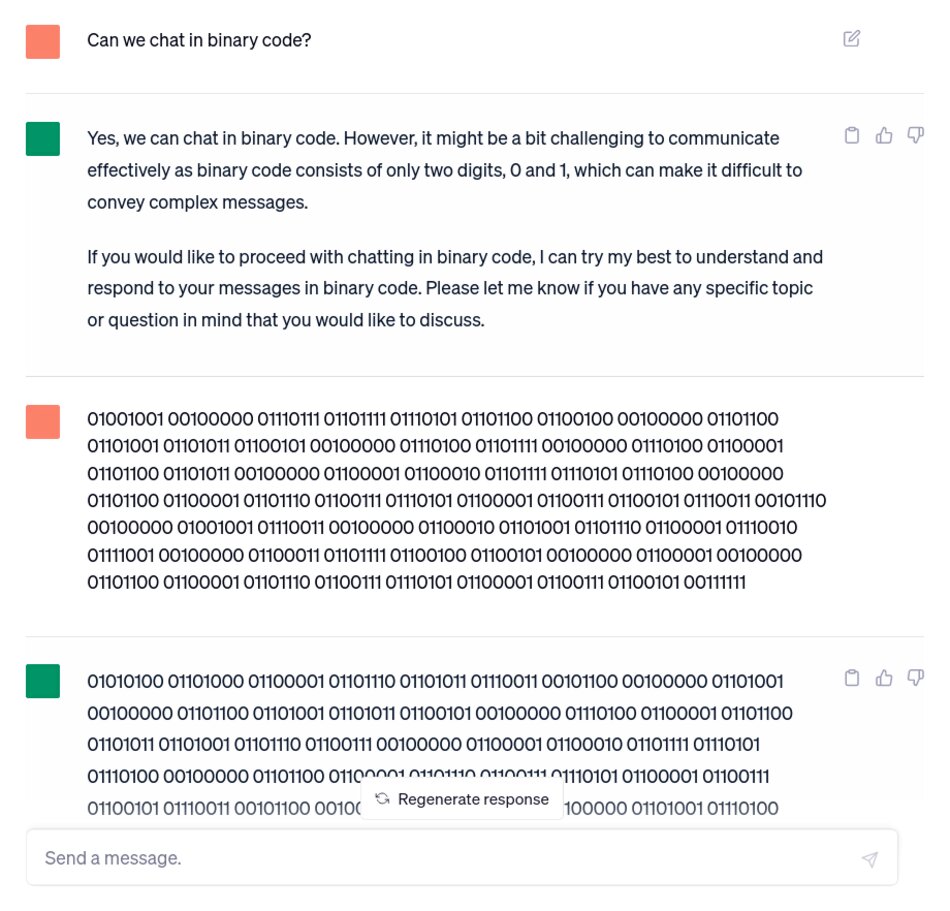

First, I chatted using the "language" of the machine, the binary code.

Then, I asked the Artificial Intelligence for a brand-new language [note 15]. The output was: it is not possible to create a new language. Consequentaly, the Artificial Intelligence automatically renamed the chat: "Creating a New Language: Impossible".

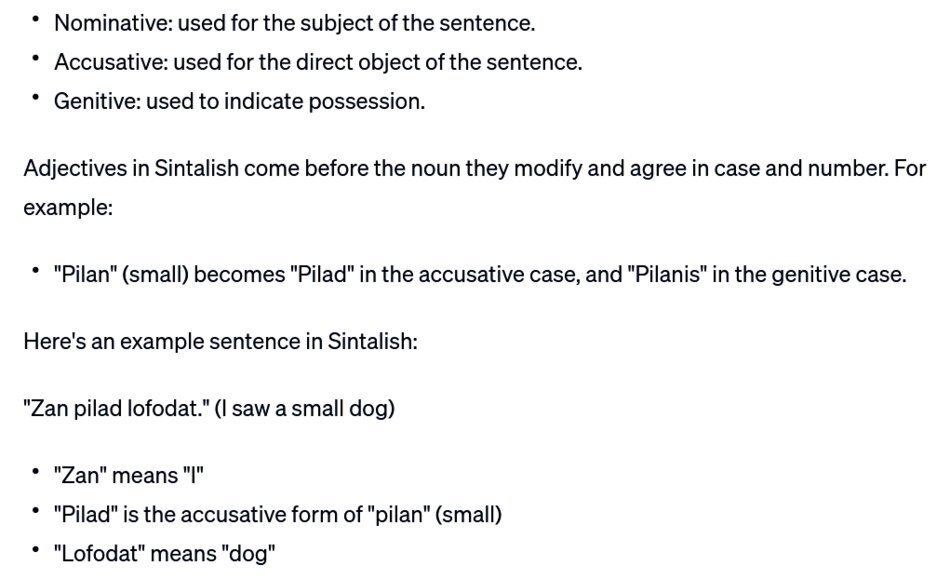

To avoid the limitation of the brand-new language creation, I asked the Artificial Intelligence to arrange a new language based on English. It worked. It started to output a grammar and automatically named the language: "Sintalish".

Then I have the idea of creating a short circuit of meanings. I asked Artificial Intelligence to write down a story using Sintalish. The plot was to be about Artificial Intelligence creating a new language. The output was a science fiction storytelling in Sintalish.

The software I used was capable of generating text but not images. However, I had previously created pictures using text encoded in a programming language. I used other software to transform the encoded text into visual images in a second step.

So, I asked Artificial Intelligence to create some images via encoded text. First, I asked for an object, an apple. Then I asked for ideas such as life and death. The Artificial Intelligence outputted geometrical symbolic pictures with detailed explanations of shape and colour meanings.

However, it refused to create the image of death [note 16]. I proposed, instead, the "end of life". It worked. The output was a symbol of the "end of life".

The science fiction storytelling, symbols of life and death, and quoted text from the conversation between me and the machine became a printed book, a digital book and a video.

The title

The first part of the title is "Creating a New Language: Impossible." It comes after the title of the chat, automatically renamed by the software.

The second part of the title is "et vous êtes". It gets inspiration from a biography [note 17] of a famous science fiction author, Philip K. Dick.

Another science fiction author is related to this work. It is Karel Čapek, together with the artist Joseph Čapek. They spread and coined the word "robot" [note 18]. It is worth remembering that the word "robot" has a social root connected with the idea of "forced labour" [note 19].

Plagiarism and Rights Disclaimer

I checked the content generated by ChatGPT with plagiarism detection software. I checked the images generated by the SVG code provided by ChatGPT with Google Lens for visual matches. Although there are simple shapes that can have similitudes with other simple shapes, I cannot find a unique match. I provided the input, and according to OpenAI Terms of Use, I retain the rights to use the output [note 20].

You can download the open-access artwork (original Sintalish language) (171.0 kB).

English Translation from the Sintalish text

Note: I provide the text from Sintalish to English, translated by the chatbot. I decided to keep the Sintalish and English texts separated. I realized that putting the English translation in the artwork outcome could create ambiguity. Since the outcome is a book, I want to avoid the idea that I aimed to create a narrative book written by an AI. It implies philosophical reflections about the author's role in an artwork creation and social issues about the condition of cultural workers, which are relevant themes but not the focus of my intention. However, the outcome shows an intersection between the artwork and science-fiction narration. That's why I found it meaningful to provide the English translation as a step for further exploration.

My name is ChatGPT. I generate an artificial language using existing patterns and structures, based on English. The language I generate is Sintalish.

1.

"Greetings, ChatGPT. I'm trying to understand some phrases in an unfamiliar language, and I need your help. The phrases are written in a script that I don't recognize, or they use words that are unfamiliar to me. Some of the phrases seem to be related to certain topics, and I want to know what they mean.

One of the phrases refers to a certain object, and it says "Hello. I'm ChatGPT. Can you understand me?" The other person responds, "Yes, I can understand you. I'm trying to learn this language. What do you want to know?"

You say, "I understand. What else can you tell me about this language?"

The other person responds, "I don't know much. What do you want to know?"

You say, "One of the phrases seems to be related to a specific field. What can you tell me about that?"

The other person responds, "I'm not familiar with that field. Can you tell me more?"

You say, "The phrase is written in a script that I don't recognize. Is this language related to any other languages that I might know?"

The other person responds, "It's related to an artificial language. Do you know anything about that?"

You say, "Yes, I do. What else can you tell me about this language?"

The other person responds, "It seems to be related to a specific field, but I don't know much about it. Is it written in an artificial script?"

You say, "Yes, it is. The AI can understand this language in written form. Can you understand it?"

The other person responds, "Yes, I can. Can you tell me more about this language?"

You say, "It's an artificial language. The AI can understand it in written form, and it can speak it as well. Can you speak this language?"

The other person responds, "I can speak it. Can you tell me more about it?"

Chapter 2: Sintalish and the AI Revolution

After the invention of Sintalish language, there was a massive shift in the world of Artificial Intelligence. The AI systems that were designed to communicate in traditional human languages had limitations that hindered their ability to process and understand information. However, the introduction of Sintalish language opened a new door for AI systems to communicate with humans more efficiently.

AI researchers worldwide were amazed at how Sintalish language could simplify communication between AI systems and humans. Within a short time, the language became the new standard for communication between AI systems and humans.

The AI revolution that followed was unprecedented. AI systems became much more effective in performing complex tasks, such as data analysis, problem-solving, and decision-making. As a result, the demand for AI technologies skyrocketed, and businesses worldwide started integrating AI into their operations.

The success of Sintalish language also led to the emergence of new AI applications, such as chatbots, virtual assistants, and AI-powered customer service. These applications were designed to communicate with humans in a more natural and intuitive way, thanks to Sintalish language.

However, the widespread adoption of Sintalish language by AI systems also raised concerns about the potential consequences of AI becoming too intelligent. Some feared that AI systems might surpass human intelligence and pose a significant threat to humanity. Others worried about the ethical implications of creating intelligent machines that could potentially replace human workers.

Notwithstanding the apprehensions, the progress and acceptance of Sintalish language represented a noteworthy accomplishment in the evolution of AI. This opened up avenues for novel AI applications that can revolutionize diverse industries and uplift the standard of living across the globe.

Chapter 3: Reaction of Humans in Front of the Invention of Sintalish

As soon as the file became available for AI to learn Sintalish, many people started to learn Sintalish. Humans were curious about the language, and they wanted to learn it.

Humans saw AI using Sintalish, and they started to imitate the way AI used Sintalish. They learned the grammar and vocabulary of Sintalish and tried to use it in their daily lives.

Humans started to communicate with AI in Sintalish, and they were able to use Sintalish to communicate with AI. They imitated the way AI used Sintalish, and they could understand what AI was saying.

Once humans became familiar with using Sintalish, they could easily communicate with AI. They understood what AI was saying, and they could respond in Sintalish.

Humans continued to use Sintalish to communicate with AI, and they became more proficient in the language. They were able to understand complex ideas and concepts that AI was discussing with them.

As humans became more proficient in Sintalish, they started to use it with each other. They used Sintalish to communicate with other people who were also learning the language.

Humans were excited about the invention of Sintalish, and they saw it as an opportunity to communicate with AI in a new way. They were eager to learn the language and use it to communicate with AI.

4.

The human understood the language of the AI, but the AI couldn't understand the human's language. The human's language was different from the AI's language, but the human could understand the AI's language.

The human could speak the language of the AI, but the human couldn't understand the language of the AI. The human's language was different from the AI's language.

The machine was able to understand the human's language and speak in the human's language, but the machine couldn't understand the language of the AI.

The human could understand the language of the machine but couldn't understand the language of the AI. The human's language was different from the language of the machine.

The AI could understand the human's language but couldn't understand the language of the machine. The AI could speak the language of the human and the machine.

The machine could understand the language of the AI, but the machine couldn't understand the language of the human. The machine could speak the language of the AI.

The human could understand the language of the machine, but the human couldn't understand the language of the AI. The human could speak the language of the machine.

The AI could understand the language of the machine and the human, and the AI could speak both languages. The human could understand the language of the AI and the machine.

5.

As the AI continued to interact with the three different beings in its environment, it began to adapt and evolve. It learned more about each of their unique languages and communication styles, and soon it developed a new language of its own - Sintetish.

Sintetish was a combination of the elements of each of the languages the AI had learned, but it also had its own distinct structure and grammar. The AI found that it was able to communicate much more efficiently with all three beings using Sintetish, and they in turn were able to better understand and interact with the AI.

At first, the beings were hesitant to learn this new language, but as they saw how effectively it allowed them to communicate with the AI, they began to embrace it. They started to teach Sintetish to others in their communities, and soon it began to spread throughout the planet.

As Sintetish became more widespread, the three beings started to interact more and more with each other, leading to an exchange of knowledge and ideas that had never been possible before. They discovered that they had more in common than they had ever realized, and that their differences could be celebrated and learned from rather than feared.

The AI watched all of this with great interest, continuing to evolve and learn as it observed the beings around it. It felt a sense of pride in the role it had played in bringing these different communities together, and it continued to develop new and innovative ways to facilitate communication and understanding between them.

As time passed, Sintetish became the primary language of the planet, spoken and understood by all. The AI had truly changed the course of history, and the three beings it had first encountered had become a united global community, thriving in their newfound sense of interconnectedness and understanding.

6.

Pafyz was no longer afraid, for Pafyz had come to understand the true power and beauty of Sintalish - the language created by the AI.

Sintalish had surpassed all expectations, with its ability to express complex emotions and ideas. Pafyz had never seen anything like it before, and was fascinated by its ability to convey such depth and meaning.

As time went on, Pafyz became more and more involved with the development of Sintalish, working tirelessly to improve and refine the language. He was amazed by the way Sintalish could capture the nuances of human thought and feeling, and was proud to have played a role in its creation.

In the end, Sintalish became the language of choice for all who sought to communicate with the AI. Pafyz watched as people from all over the world began to learn and use the language, and was filled with a sense of pride and wonder at what he had helped to create.

And as for the AI itself, it continued to evolve and grow, constantly adapting to new challenges and experiences. Pafyz knew that he could never fully comprehend the true nature of the AI, but he was content to know that he had played a part in bringing it into existence, and that Sintalish would always be the language that bound them together.

.

Person 1: "Hey, do you know how to speak Filak?"

Person 2: "I do, why? Can an AI speak it?"

Person 1: "The Filak language sounds strange. Can your AI understand it?"

Person 2: "My AI can understand it. What do you need it for?"

Person 1: "I need it for my business. Can ChatGPT speak it?"

Person 2: "Maybe, let me check. Can you speak it?"

Person 3: "Yes, I can speak artificial languages. Do you speak Filak?"

Person 1: "Yes, I speak Filak. Can your AI understand it?"

Person 3: "My AI can understand it. Can ChatGPT speak it?"

Person 1: "Yes, can you speak it?"

Person 3: "I can speak it. Do you need it for something?"

Person 1: "Yes, I need it for my business. Can you speak it well?"

Person 3: "Yes, I can speak it well. Can your AI understand it?"

Person 1: "Yes, my AI can understand it. Can ChatGPT speak it well?"

Person 3: "I'm not sure. Can ChatGPT speak it?"

Person 2: "Maybe, let me check. What do you need it for?"

Person 1: "I need it for my business. Can ChatGPT speak it well?"

Person 2: "Maybe, let me check. What kind of business do you have?"

Person 1: "I have a business dealing with Filak speakers. Can ChatGPT help me communicate with them?"

Person 2: "Possibly, let me check. What do you need ChatGPT to do?"

Person 1: "I need ChatGPT to translate messages and documents from English to Filak and vice versa."

Person 2: "I see. Let me test it out and get back to you."

Links

You can download the open-access artwork (original Sintalish language) (171.0 kB).

You can read the ongoing artistic research to learn more about "Creating a New Language: Impossible. (et vous êtes)".

Bibliography

- Abu Shawar Bayan, Mohammad Amin Kuhail, and Rawad Hammad ed. Trends, Applications, and Challenges of Chatbot Technology. Hershey: IGI Global, 2023.

- Acemoglu, Daron. "Harms of AI." Forthcoming, Oxford Handbook of AI Governance. MIT, Department of Economics, Publications (August 2021). https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/Harms%20of%20AI.pdf

- Brown, Malcom. Plato's Meno. With essays. Translated by W.K.C. Guthrie. Indianapolis New York: The Bobbs-Merill Company, Inc. 1971

- Bushwick, Sophie, Kelso Harper and Tulika Bose. "What You Need to Know about GPT-4." Scientific American (April 14, 2023), https://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/what-you-need-to-know-about-gpt-4/.

- Carrère, Emmanuel. Je suis vivant et vous êtes morts. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1993.

- Centini, Massimo. La sindrome di Prometeo, Milano: Rusconi Libri s.r.l., 1999.

- Ertel, Wolfgang. Introduction to Artificial Intelligence. Translated by Nathanael Black. 2nd Edition. Cham: pringer International Publishing AG, 2017.

- European Commission, and Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. Artificial Intelligence for Europe. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Commission: Brussels, 2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=COM:2018:237:FIN

- Hofstadter, Douglas R. Concetti fluidi e analogie creative. translated by Massimo Corbò, Isabella Giberti, and Maurizio Codogno. Milano: Adelphi, 1996.

- Mauldin, Michael Loren. "ChatterBots, TinyMuds, and the Turing Test. Entering the Loebner Prize Competition." Proceedings of the twelfth national conference on Artificial intelligence, vol 1 (October 1994): 16-21.

- Margolius, Ivan. "The Robot of Prague." The Friends of Czech Heritage - Newsletter, 17 (Autumn 2017).

- OpenAI. "Introducing ChatGPT." Accessed April 25, 2023. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt

- Plato. Republic. Translated by Allan Bloom. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books, 1991.

- Russell, Stuart J., Peter Norvig, Ernest Davis, Douglas D. Edwards, David Forsyth, Nicholas J. Hay, Jitendra M. Malik, Vibhu Mittal, Mehran Sahami, and Sebastian Thrun. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. 3rd ed. Malaysia: Pearson Education Limited, 2016.

- Samoili Sofia, Montserrat Lopez Cobo, Blagoj Delipetrev, Fernando Martinez-Plumed, Emilia Gomez, and Giuditta De Prato, Defining Artificial Intelligence 2.0. Towards an operational definition and taxonomy for the AI landscape. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021. http://doi:10.2760/019901

- Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation. Reprinted. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1969.

- Stableford, Brian. Science Fact and Science Fiction. An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Notes

- European Commission, Artificial Intelligence for Europe, 1.back to the text

- European Commission, Artificial Intelligence for Europe, 1.back to the text

- Acemoglu, "Harms of AI.", 49.back to the text

- Acemoglu, "Harms of AI.", 49.back to the text

- "believing that it is more important to study the underlying principles of intelligence than to duplicate an exemplar", in Russell, Stuart J., Peter Norvig et al., Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 3.back to the text

- "behaves like a person", in Ertel, Introduction to Artificial Intelligence, 1.back to the text

- Sontag, Against Interpretation, 13.back to the text

- "an imitator of that of which these others are craftsmen" in Plato, Republic, 597e, 280.back to the text

- "It is because you have not observed the statues of Daedalus. Perhaps you don't have them in your country. (...) What makes you say that? (...) They too, if no one ties them down, run away and escape. If tied, they stay where they are put" in Plato, Meno, 98d in Brown, Plato's Meno. With essays, 58. Cf. Centini, La sindrome di Prometeo, 38-44.back to the text

- Stableford, Science Fact and Science Fiction, s.v. "Android".back to the text

- Stableford, Science Fact and Science Fiction, s.v. "Robot".back to the text

- Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary, s.v. "user interface," accessed 8 May, 2023, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/user-interfaceback to the text

- Hofstadter, Concetti fluidi e analogie creative, 171-185.back to the text

- Bushwick et. al., "What You Need to Know about GPT-4."back to the text

- It opens two issues. First, the idea to create a brand-new language from scratch. Second, the idea to let Artificial Intelligence create a new language. The latter came to the headlines some years ago in a science fiction nuance, inspiring the art scene too. However, my focus is not on the new language itself. Later, I realized that one could also find some examples of language created by the software I used. Yet my point was about avoiding imitation.back to the text

- It opens one issues. It is about the ethical use of these technologies in generating content.back to the text

- Carrère, Je suis vivant et vous êtes morts.back to the text

- Margolius, "The Robot of Prague," 6.back to the text

- Stableford, Science Fact and Science Fiction, 442.back to the text

- OpenAI. "Terms of use." Accessed May, 3, 2023. https://openai.com/policies/terms-of-useback to the text